Ed. note: This piece was originally written as prose but has also been posted as Twitter-native thread. I present it here with paragraphs in their original, rather than tweet-sized forms.

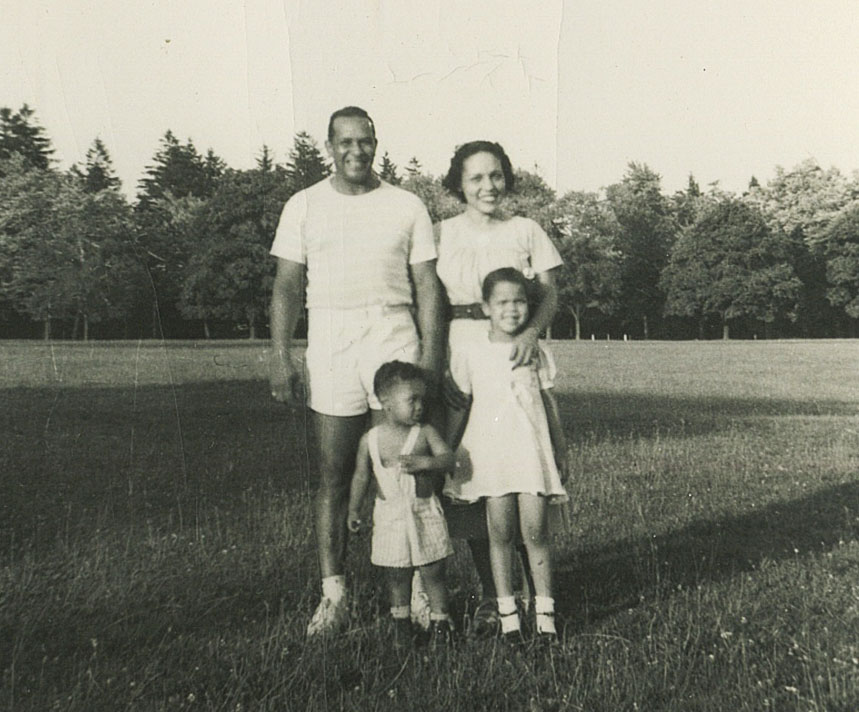

In my early 20s I subscribed to Sports Illustrated and still regret throwing away the LeBron James “Chosen One” cover. We’d had the magazine around the house growing up and I always looked forward to the next issue, to Mike Tyson in plain black trunks, Elle Macpherson in teal. My father, a journalist himself, once told me that sports were good because they were the first place where a black man could compete with a white man on an even playing field.

As an adult, the writer Gary Smith moved me beyond words. His feature about the Darling twins, one of whom died in football practice at a brand-name university wrecked me for a solid half hour. “He bought two cakes,” I blubbered between sobs after reading of the surviving twin’s birthday, “he bought two cakes.”

Smith is a master at endings. One final stitch to cinch the whole thing together. I bought his first anthology, read it twice.

The sports writing landscape is as strong as ever – the web has empowered a great many voices, like @netw3rk and @freedarko. But the authority of a small, edited volume serving us the final word is long gone. I find myself listening to the podcast of two fellows broadcasting from a garage to an audience of three. Or maybe it’s just that the end of scarcity has trampled my ability to savor words. The faucet is always on, and so I am always drunk on cheap, boxed sports wine. I mean, writing.

In the era of the tweet, of punchline rap, the succinct ones dominate.

And when you look away from sports, back to things that “really matter,” the writers chopping away at growling winds of injustice armed only with hatchets, it’s enough to run back to the balmier pastures of Howard Beck and Bill Simmons, refreshing their feeds, a lab rat on meth.

I lost football, the game I first loved, because of a racist team name, rampant commercialism, concussions, unfair labor practices, and the response to Colin Kaepernick. I revel in the aesthetics of a perfect jumpshot while white nationalists throw gang signs at Supreme Court confimation hearings. And can’t find the person to tell me that the jumpshot will beat the bigot.

Words are not the blanket they once were. The even playing fields are shrinking up. We stand at the plate waving at hundred mile an hour fastballs with toothpics for bats; they splinter in our hands.

Sometimes it feels like world has gone to Hell these last few years. Fighting back, dragging this place towards normal, to good, like an ox with a thick rope through its teeth, pulling the thing back to sanity is our job as writers and artists. It’s the job of scientists and politicians, activists and educators. Journalists and plumbers. It’s the job of citizens. I’m not very good working with these crude tools. And there aren’t enough of us to plow this whole field. Not yet anyway. Not in nice rows where each plant breaks through the dirt at a different angle, but they all grow into perfect eight foot stalks of sweet summer corn.

The plants swish and sway in the breeze. Like the net after Steph Curry hit that game-winner against OKC and Crip Walked afterwards and one of the broadcasters in the postgame said, “I’ve never seen a man be so free on a basketball court.”

Sports writing taught me about writing. I miss it. The tweets will suffice and there’s a bigger game afoot.

The competition is fierce, unrelenting. Their uniforms are the black robes of judges, police blues, pantsuits and the pinstripes of tycoons. The playing field stretches out in every direction, to gray mountain passes crammed with boulders and deep canyons in mercury.

There are no pages to house the story. The cover pic of an eighteen-year-old with cornrows, crossover cold as the dickens, and a can’t lose smile just flashed by on Instagram. The caption reads, “we gon’ make it.” And I believe her.