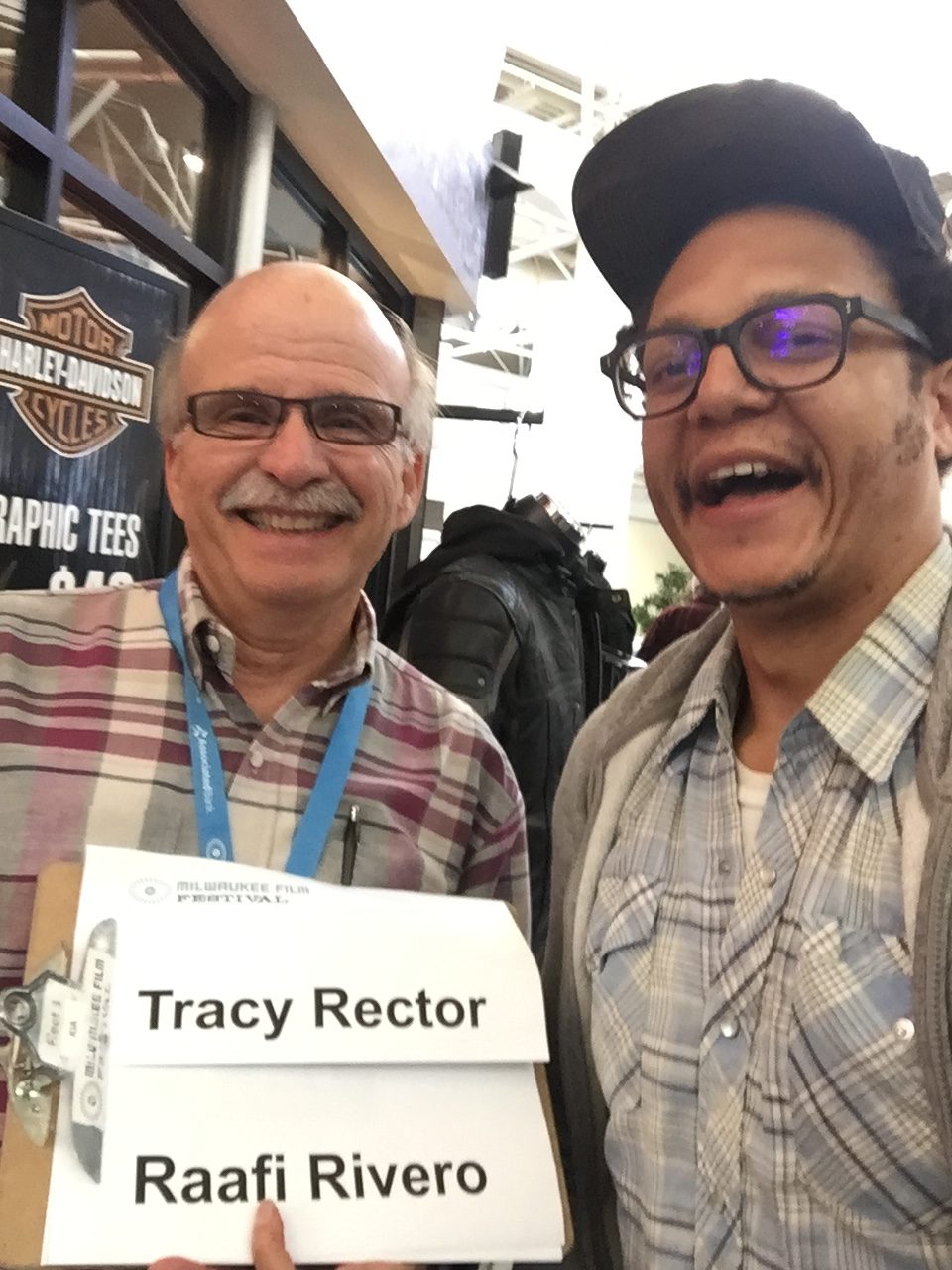

Striding off the plane and toward the Milwaukee Film Festival won’t be like heading to L.A. a year ago, having barely slept and giddy for a date with destiny. The premiere of a director’s first feature film will always be special, mine certainly was. I’m not coming to Milwaukee a seasoned vet either, more of an early-mid-career type of vibe. In a snatch of time before putting my phone into airplane mode I learn that the first two screenings have sold out of advance tickets. On the other end of the flight I learn that a driver named Campion is waiting to pick me up near the Harley Davidson store in the terminal, the first of many pleasant surprises.

This year has been difficult. I have wrestled with change in my business and personal relationships. A week ago I turned 40, a natural moment for both celebration and reflection. What harbingers will five days on Lake Michigan offer?

FRIDAY

More than one person tells me that Milwaukee has recently been ranked in the top five most segregated cities in the country. Walking from the hotel to the festival that first afternoon I certainly feel the strain of my presence in this new place. One of my favorite things to do is to walk through a strange city with a camera. Being six feet tall and black means that consequence ripples out from my presence in many of these spaces. People’s faces tighten. They look away. They cross the street. I walk and take pictures.

I arrive at the festival lounge, introduce myself to folks, make awkward small-talk, and wait for something to happen. I’m not sure who my tribe is here. My screening is at 8 and there is time to kill. I meet Meagan, who’ll be driving me to the screening later.

Flashback to LAFF 2016: walking down a corridor of the Arclight Culver City to the world premiere of 72 Hours. The festival’s coordinator wanted to be there to escort me – she chose my film. She nods to a line of people standing outside the theater and says, “don’t you want to take a picture of all the people lined up to see your movie?”

Present day: I’ve never been driven to one of my screenings before. A week ago in DC I helped clear chairs before the movie played in a book store. Now I’m riding in a factory-fresh Lincoln and there’s a line of people outside the theater. I did very little promotion for this screening. These people came out on their own. My heart leaps. And as dorky as it must look, I hop from the vehicle and start snapping pictures of the people in line. Wow.

I’ve now seen three versions of the film play in seven cities. There are a few reliable laughs. Moments when we lose a chunk of the crowd and others where we win back some of what was lost. The film fades to black and I know that a rocky journey to a new perspective has been made by both the characters and audience. Not everybody likes the view, but enough people do, I suppose. I can expect to be complimented on the film’s soundtrack and to be asked what the question mark in the title means. I am ridiculously proud of this imperfect little film. I know there are things I can do better. I know I couldn’t have done any more.

The screening goes well and most people stay for the Q&A. The last question deals with a violent sexual encounter that happens in the film. I am grateful that the questioner chose not to frame it as an attack. Of the many ways I’ve imagined someone asking this question and my response to it, I am lucky here in that I am able to answer a story question: easy, a process question: easy enough, and the why-even-film-the-scene question: more difficult.

crowd for the first screening

with the Black Lens crew that made the screenings and panel such a success

SATURDAY

I walk and photograph, taking a different route to the festival, and head to see Ken Loach’s I, Daniel Blake. Starbucks, a smoke, and I am once again staring at a block of free time. I walk and photograph some more. One of the homes along my route has a sign in the front yard advertising it as a place where, among other worthwhile causes, black lives matter. I feel neither off-put nor heartened by this news.

Schumann’s Bar Talks teaches many things about cocktails and cocktail makers as we follow the legendary bartender/owner, Charles Schumann, to some of the world’s finest bars. During the series of conversations that make up the body of the film, opposing viewpoints are often put on equal footing, giving the story unexpected depth and texture. Like a good cocktail.

I have a great conversation with Liz, the person who first contacted me from the festival and who, I learn, put the film in front of the programmers. (DJ Shadow … Meets His Maker). Donte, one of the programmers who selected the film, introduces me to Larenz Tate who’s in town for a screening of Love Jones. Robin invites me to an after-party. I meet more of the staff. And for a brief moment the festival turns inside-out. I visit one of the back rooms. I walk with a group of staff to another bar. I am a person who knows people here. I hear more recommendations for Milwaukee’s famous dive bar scene and head off to River West to see what’s next.

with some of the festival staff

At a bar and wing place the night’s MC urges the audience to compete in a “chickenhead” dance contest. At another spot I groove with a woman near the jukebox as gem after gem pumps into the bar. She’s at least ten years my senior, and the songs are old enough to be parents. I ask my ride home stop by a late night food truck and order the plate of ribs.

And the winner of the chickenhead dancing contest is…

SUNDAY

I walk a different route to the lounge in the morning. Today is my best chance to see a bunch of movies. In spite of the eight checks I make in the festival guide I am only able to see three features and two of the virtual reality shorts: Like Cotton Twines, Life of the Party, Love and Saucers (hit the L section pretty hard, I guess), and the shorts Eagle Bone (Ch’aak’ S’aagi) and The Fight for Falluja.

In between films I eat, drink, joke. Afterwards my new friend, Mia, drives to a cocktail bar. We’d spoken briefly at an after-party the first night then sat next to each other at a screening today, now we’re friends. I can’t stay out late; there’s a classroom full of middle schoolers to visit in the morning. But, sure, twist my arm. One more cocktail.

MONDAY is my biggest day.

More than other festivals I’ve attended, this one offers multiple inroads to the community outside of screenings. Before leaving town I speak at two schools, make a radio appearance, and sit on a panel.

Most of those things will happen today. The middle school is first, I also signed up for a cinematography workshop in the afternoon, then my second screening, then the panel.

Buzz picks me up at 8:15 and we head to Lincoln Center of the Arts – a building I photographed on Friday. I can remember adults coming to classes when I was in school but little of what they said. Mainly what I remember is how different they were from one another. In sixth grade a reporter from The Washington Times visited class. He was skinny, maybe a little nerdy, and precise with his language. An architect visited another time, confident and brusque. A blind German diplomat, warm and clever.

I’d met Lee the first day during a moment filled with quick intros and rushed handshakes, which is to say I hadn’t really met him at all. Today we strike up a conversation in the lounge and before the runway is even built we’re flying through topics: film talk leads to community engagement and creative placemaking, New Orleans and drumming in marches, redlining and institutional racism, urban design and public space, political action and Catalonia, writing routines and thesis committees.

Arriving late to Wyatt Garfield’s cinematography master class, I’m embarassed and intrigued. He’s turned the space into a black box and asks how many of us have made a pinhole camera. A moment later the entire room is turned into one when the artificial light is turned off and he cuts a small hole in the window blacking. I learn more about the direction and bouncing of light in that one hour than in any single hour of my life.

This is the first festival where we’ve had posters made. I ask two people in the lobby of the theater to pose with me. Yeah!

crowd for the second screening

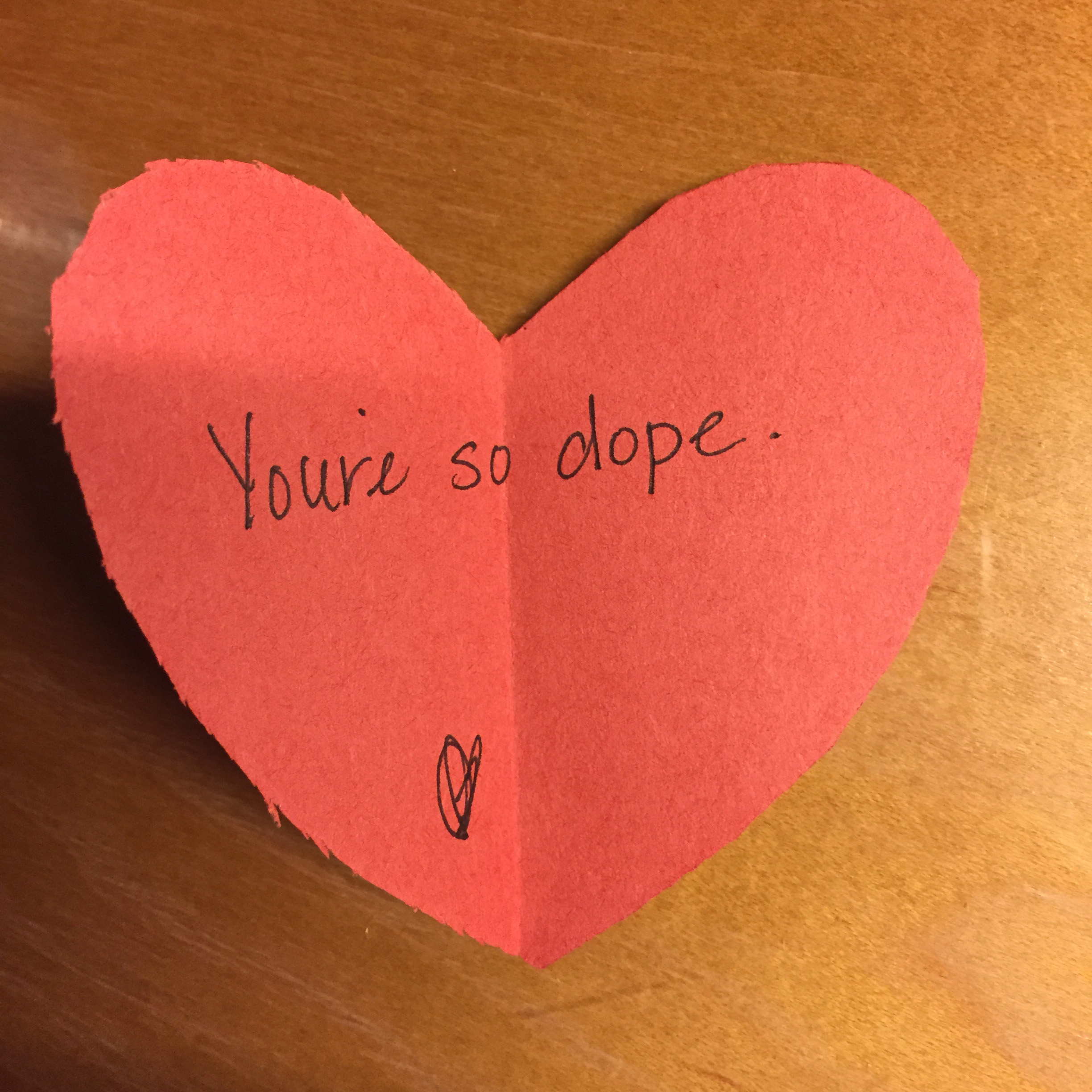

After my screening I walk to The Back Room where I’ll be on a panel called Black Love Through a Black Lens. I try to conceal my shaking left leg. The place is packed. I don’t think anyone expected such a good turnout, but Love Jones played the other day (and my film, ha), and people are primed. The moderator Daysha is a star – reframing questions with wit and finesse, taking the temperature of the panel, the crowd, modulating the energy. The speakers are intelligent, soulful. My jokes work. And the serious parts, too. And while the event isn’t explicitly about my film the topic of love in black film weaves through the conversation just enough. I’m having a blast. From the stage I can see that every seat is full and several rows of people stand in the back. Later, someone says this has been the best-attended event in the history of the venue. The DJ starts up after the talking’s through and there’s a table where people write messages on cutout hearts. Someone approaches and hands me this:

TUESDAY

Because my film is about high-schoolers and is adapted from a documentary made by someone in high-school, there are plenty of ways to connect with students. I’m at South Milwaukee high-school for a Reel Talk moderated by Cara. We show the class my trailer and a clip from the short documentary that inspired 72 Hours. I can feel something special in the room: a group of mainly white teens in Milwaukee watching video of a group of mainly black teens in Brooklyn. There is a sense of recognition flowing from screen to audience that I feel lucky to witness. I show slices of my work: an experimental piece, a documentary piece, a romantic comedy. The conversation hits practical stuff like what it’s like to do this for a living, creative questions, and what’s your favorite movie? I make it through without cursing, unless you count describing something as a “crazy-ass film.”

I arrive near the festival for brunch with Rubin Whitmore, the director of Life of the Party. He makes a quick introduction to the festival’s director, Jonathan, and as Rubin and I return to our table, Cara who just moderated my talk with the students arrives for lunch with Jonathan. This strikes me as the quintessential film festival moment: people meeting to talk film, to talk business, the “oh-you-know-that-person-too?” waves across the room.

In my interview last fall with Joan Clos, Executive Director of UN-Habitat and a former mayor of Barcelona, he had this to say:

“I like this definition of a city: that a city is a place where you find what you are not looking for. [I like] This kind of serendipity, or these emergent properties of a city that create movements that nobody has designed.”

In its platonic ideal I believe a film festival is a city in microcosm, organized around the watching and talking about movies. It creates these serendipitous interactions between the community and the artists and facilitates the connections between disparate pockets of the community itself.

Elly drives me to WNOV – where I’m to appear on-air with Michele Bryant. As I walk into the studio Michele is being harangued by a caller who suggests that black americans are not sufficiently grateful for being liberated from slavery. It is his third call to the station that day. She deftly makes the switch from racial politics to film talk and it’s fun to try on a few guises – firebrand, cultural analyst, thoughtful artist – during my 45 minutes on the air.

Dinner with Buzz and a young filmmaker named Vonnie, another intellectual deep dive with Lee, and a broader film talk with Alyx, Justin, and Petey before it’s time to go drink.

Alyx and I have chatted in brief snatches throughout the four days. She helps run another film festival in Oklahoma City and now I want to play there as well. We head to a spy-themed bar, talk more film, and laugh at ourselves a little bit. One last selfie, and my hotel is only a block away. Perfect last night in Milwaukee.

Campion picks me up in the morning, full circle, and the conversation moves from film to sailing, international travel, and finally the importance of culture. Amen.