“Miiiiiiran los plieeeegues,” he would plead while dying a thousand little deaths along the way — Loooook at the foooolds. He was the only person besides Martin Luther King, Jr. that I’d ever heard speak with vibrato. And I got to hear him every Wednesday afternoon in art history class. “Miran los pliegues,” he would exclaim with each new slide. And his whole body shimmied with the samba of his voice – or Sardana, it was Spain after all. I had been learning a new language at the time, Spanish, and living in Barcelona. Miran los pliegues is probably the first phrase that made more sense to me in that language than in English. To this day, I can’t imagine any of my stiff high school teachers or college professors loving folds so much that to merely talk about them would be to sing.

The folds in cloth, the details, betray an artist’s ability and mastery. He explained that it wasn’t until Michelangelo that a sculptor could create folds as well as the Greek masters had. Miran los pliegues! And the class would giggle. But we looked at them in spite of ourselves. Plee-AY-gase. Pliegues. Somewhere along the way, much later, I would have to translate them back into English, but I never had as much use for them once they became folds.

Señor Vilalta had been a legend even before I had arrived at his school and in his country. There is a wonderful teacher there, my Spanish teacher advised the year before as I considered the program. You’ll love Señor Vilalta, another classmate pressed me to apply.

Profesor Vilalta’s first name was Ángel. Though he taught his Wednesday class the French term faux amis, false friends, meaning words that sound the same in different languages but carry different meanings, there was little doubt that his beatific aura needed translation. “Petagay Rowe,” he would chirp the name of a classmate in his best British accent, “me encanta esa nombre.” Because he could, he would smile and speak the queen’s English from time to time, “Hello, how are you. My name is Petagay Rowe. Ay, me encanta, what a beautiful name,” and back to the Quattrocento, the Rococo, the impresionistas.

“Apaga la luz!” he would command midway through a lecture — turn off the lights, or literally, extinguish the light. He would probably have been cradling a slide carousel in his arms for a few minutes, and inching toward his projector in the middle of the room. “Apaga la luz,” he would often repeat after having added continuation after continuation to the original thought – each more pressing than the one that proceeded it – finally arriving at the projector. A student would stand to lower the window shade while the one closest to the door would reach up and flip the light switch to off. And in a darkened classroom, on the high seas of a voice that existed only in squalls and swoons, I learned that the folds, señores y señoras, ladies and gentlemen, los detalles, the details, are where you find the mastery.

Years later in college I needed an art history credit to satisfy my graduation requirements. I was a senior and had registered for the art history pu-pu platter that was offered to first-years. The professor showed slides, but he never said Paf! “Boom!” when something great splashed onto the screen. Please take a second to admire Praxiteles’ detail in the folds of Hermes’ robe. I drifted off to sleep. After two weeks I’d had enough. I told the professors in charge of my department that I studied art history in high school. They rolled their eyes. I couldn’t explain to them — in an office crammed with books and the fetid tenor of intellectual pomp — that Profesor Vilalta once taught me that Miles Davis, if he had been a painter, might have been the greatest painter in the world. Eventually, skeptically, they relented. But there was no way for them to understand what I’d learned from the vibrant bearded man in Barcelona.

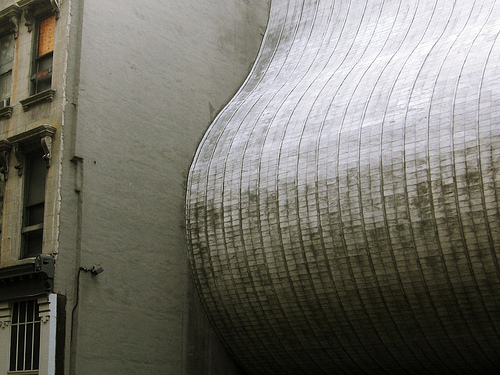

In a city bursting with art and barely large enough to contain the heart of Ángel Vilalta, I learned that folds and shadows, the shapes of hands and the lines in architecture are footfalls, breaths in a lifetime of appreciating art. I live in another city now. It is a place where conflicting lines and forms raise themselves up like gale-force winds. Still, some part of me translates much of what I see into the vibrato of a passionate voice that lives and dies on the shores of each canvas. And in quiet moments I know only to look more deeply into the folds, and to carry on my way.

how bout some updates!

I too learned to love art history b/c of Senor Vilalta. Spain ’93

Thanks for the memories.

The phrase “force of nature” can accurately be applied to his personality.